I’m beginning my series on the narrative of Muhammad’s life at the cave where Islam began. This is perhaps the most momentous event in the history of the world for more than a billion people alive today, but only a handful understand how it would have been understood by the polytheists (Arab pagans), Jews, and Christians of Muhammad’s time.

This is the fullest hadith about the circumstances of the first revelation. Everything in parenthesis is an interpolation of the translator–it is not in the original hadith.

Narrated Aisha:

The commencement of the Divine Inspiration to Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) was in the form of good righteous (true) dreams in his sleep. He never had a dream but that it came true like bright day light. He used to go in seclusion (the cave of) Hira where he used to worship (Allah Alone) continuously for many (days) nights. He used to take with him the journey food for that (stay) and then come back to (his wife) Khadija to take his food like-wise again for another period to stay, till suddenly the Truth descended upon him while he was in the cave of Hira.

The angel came to him in it and asked him to read. The Prophet (ﷺ) replied, “I do not know how to read.”

(The Prophet (ﷺ) added), “The angel caught me (forcefully) and pressed me so hard that I could not bear it anymore. He then released me and again asked me to read, and I replied, “I do not know how to read,” whereupon he caught me again and pressed me a second time till I could not bear it anymore. He then released me and asked me again to read, but again I replied, “I do not know how to read (or, what shall I read?).”

Thereupon he caught me for the third time and pressed me and then released me and said, “Read: In the Name of your Lord, Who has created (all that exists). Has created man from a clot. Read and Your Lord is Most Generous…up to…….that which he knew not.” (96.5)

Sahih Bukhari Hadith 6982

What, exactly, is going on here? What meaning would this have for the Arabs? How did Muhammad interpret it at the time? And how would Christians and Jews interpret it?

First, we must reverse the additions of Islamic scholars who try to insist that Muhammad (and sometimes all of his direct ancestors!) were virtuous monotheists who worshipped only Allah. The stories that try to push this narrative are countered by many more that show how impossible this was. All the anachronistic exclamations of “By Allah!” and so on in the ahadith and sirat are transparent attempts to make people from the Time of Ignorance appear not to be committing shirk, or polytheism, which is held to be the worst sin in Islam. The insertion of Allah here by the translator is yet another case of Islamic scholars being uncomfortable with Muhammad’s roots and ritual practices before the revelation. There is no actual basis for this anachronism.

Second, we have to understand that the word often translated “Read!” really means something more like “Call words!”–that could be a command to read something aloud or recite something memorized. Muhammad is illiterate. He can’t call words from paper, only from memory. He doesn’t know here what he’s supposed to call, or else, he is protesting that he can’t call from paper because he can’t read–what’s going on isn’t exactly clear.

With that settled, we can move on.

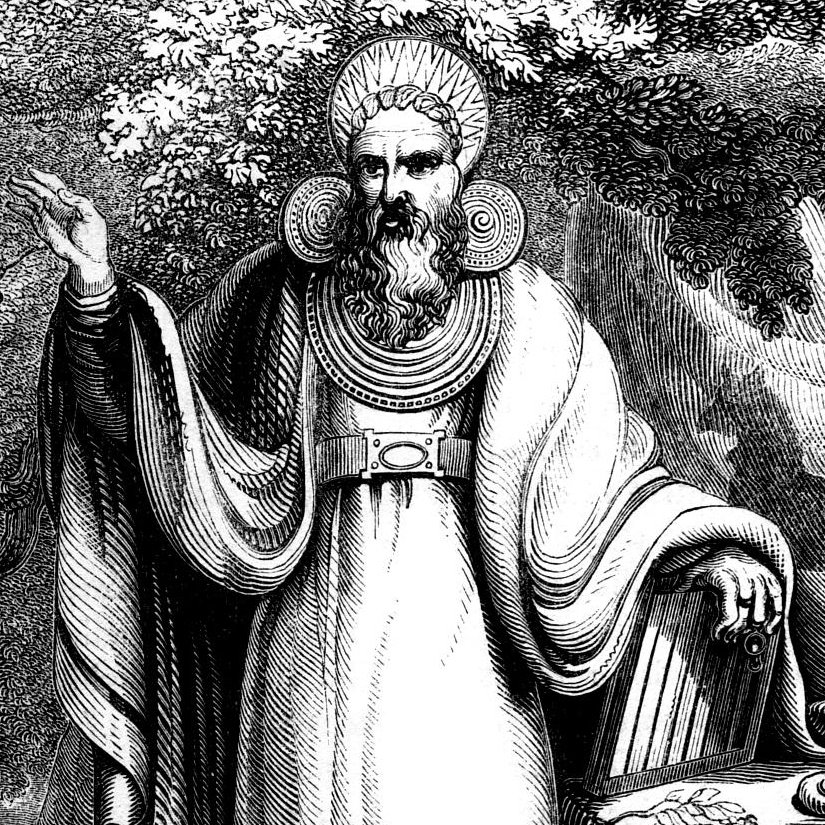

Hira: A Place of Revelation from the Underworld

We begin the hadith with the purpose of the trip: Muhammad went to the cave of Hira in order to have religious dreams. Spiritual, religious, or prophetic dreaming has ancient precedents, as does going to specific places in search of these dreams. Most people know this.

But why a cave? This is something that every ancient would know but most moderns do not. Caves were specifically seen by the ancients as being spiritually connected to the underworld, where supernatural Powers dwelt. It’s important to understand that the cosmology of the educated classes was nonliteral, just as ours is. The people who formulated ideas in these terms didn’t think that you could reach the underworld if you just dug far enough–it was another dimension that was intellectually organized as being below the human plane, but in another realm. (An easy parallel for moderns is to realize that you can be absolutely serious about saying that you love someone with all of your heart, and yet you don’t think that a heart transplant would make you not love them anymore.)

Despite this nonliteral organization of nonphysical realms, ancient people believed, however, that there were physical places that were spiritually closer to another world by virtue of their location and that were more likely to invite supernatural intervention to connect the physical with the metaphysical. Caves were close to the spiritual underworld. Mountaintops were close to the spiritual heaven. The material world was cosmologically between the two.

I’m going to use the very (perhaps even excessively) literal translation of the generic use of ‘elohim’ as Powers to explain both pagan and Judeo-Christian cosmology. The word can be alternatively translated as Mighty Ones or Strengths or Forces. I am capitalizing it only for the sake of clarity, not respect. A Power was any immortal, supernatural being. In ancient Judeo-Christian terminology, these would include the little-g-gods of the pagans (who are corrupted and rebellious Powers–Christians would come to call them all “demons,” and you can, too, if that makes you feel more comfortable), the seraphim, the cherubim, and angels (though angel is a job description, not just a specific being). This category also included the immortal spirits (“breaths”), souls, and/or shades of the dead. The pagans would heartily agree with this.

The God of the Abraham was also a Power, by definition. In fact, the most common term for the God of Abraham in the Bible (or Tanakh) was the generic Elohim. While God is singular, a plural form is used because he is the Power of Powers, or the Sum and Source of all Powers, or the Ultimate Power. (For example, what we see in and English Bible as “God goes” could actually be hyperliterally translated a “Mighty Ones goes”–clearly a singular use because of the verb form “goes” is singular even though the noun itself is plural. Many Christians, of course, also see this as a prefiguration of the Trinity–this reading will get plenty of unhappy comments, but nevertheless, it’s a reading.)

If there are many Powers, how is the God of Abraham different? Well, this is encapsulated in a name–or rather, the Name. The Hebrew name of the God of Abraham is Yahweh. It is related to his introduction of himself as “‘ehyeh ‘asher ‘ehyeh,” which means “I am (or will be) who/that I am (or will be).” This is a statement of not just being above the confines of ordinary corruptible material existence (something any Power could claim) but of pre-existence and eternality. Changing this to third person will yield “yihweh”–that’s similar to Yahweh but not quite there. (We are certain of the vocalization of “Yah” because it is used many times as a less sacred contraction for Yahweh. The “yeh” element often became “weh” in many conjugations, so “yihweh” is interchangeable with “yihyeh.”) The one conjugation that yields “Yahweh” in the required conjunction (third person, singular, and imperfect, if you care) is the Hipil causative stem. So “Yahweh” must mean “He-Causes-To-Be,” or “He-Causes-Being.” The only objection to this rendering is that we don’t actually have “yahweh” used as as a common verb in that particular conjugation in the Bible, to which I say…of course not. To expect it there would be to entirely misunderstand ancient Jewish culture. Once God has staked a sacred claim to that verb form, you don’t just get to sling it around casually anymore, and it’s not like you can’t express the same thought in other ways. The very absence of this particular form is actually evidence for its meaning, not against it.

Because the God of Abraham is the Eternal One, Yahweh is necessarily the Creator–using Greek terminology of more than a thousand years later, the Prime Mover. Ancient Judeo-Christian cosmology does not deny the existence of other Powers, but all other Powers are created beings and are lesser and derivative. There is only one eternal Creator Yahweh.

[Note: The basis for the following theology is philosophically complicated and relates to the recognition of objective ethics, which then demands the existence of a good, ultimate Creator, issues which go well beyond the scope of this article. Now it is necessary only to understand that this is how the Judeo-Christian God is conceptualized, not for you to agree with it.]

Realizing this, the ancient Jews and Christians knew that the Creator Yahweh must be fully transcendent and incorruptible in the moral as well as the material sense. This is why his Name, which encapsulates his nature, is so important in the Old Testament (Tanakh) and also why the name became treated as more and more sacred as time went on. Humans are like Yahweh in two important ways: they are made in the image of God, and they have gained moral discernment, which is something they share with all other Powers but not with animals. That is, human beings can tell that there is such a thing as good and that there is such a thing as evil. Animals, even the smartest animals, do not have existential awareness that a two-year-old child is capable of formulating. Humans share this with their Creator and also with the lesser, created Powers. And like the created Powers, humans have the free will to choose evil even when they know what is good.

According to the Judeo-Christian cosmology, because the lesser Powers are corruptible, they are not deserving of worship any more than humans are (who are also Powers insofar as they have immortal spirits). This denial of worship to humans and non-human Powers is linked: pagans have never had problems with worshipping the Powers of dead or important humans, while avoiding this worship is a frequent concern of those who believe in a perfect, incorruptible, and ultimate Creator.

Lesser Powers that are righteous would not ask for worship any more than a righteous human would ask people to worship him. We see the righteous Powers in any number of inspired scenes in the Bible (and Tanakh) where the Creator is surrounded by his divine court and in the various references to the messengers (in English, angels) of God. Righteous Powers, then, are part of the court of God and pertain to the heavenly realm.

Rebellious Powers, however, do not turn their worship and obedience to the Creator but seek worship for themselves, turning and perverting the act of sacrifice into a kind of self-glorification.

In the Judeo-Christian view, then, all Powers that sought worship and set themselves up in the place of the ultimate Creator were by their very natures corrupt. In modern English, we often lump all these various corrupted Powers under the name “demons,” but the Greek word was originally a neutral one to pagans just meaning a lesser sort of god or soul that even included the immortal souls of men–essentially, again, a meaning of lesser Powers. Similarly, we lump all the obedient Powers under the name “angels,” even though (as I mentioned above) an angel was the name of the job (messenger) that the most minor Powers often had.

Jews, Christians, and pagans all agreed that many shades of the dead dwelled in a part of the underworld, which was seen as a dark, cold, and chaotic place, associated poetically with the primordial chaos of waters or oceans. This could be called Hades (Greek) or Sheol (Hebrew). (Sheol also means literally the “pit” and can mean simply the grave as well as an underworld, which can add considerable ambiguity to the meaning.) Despite its watery associations, the spirits of the dead are often portrayed as always thirsty in pagan sources. (The differentiation between the bosom of Abraham, heaven/heaven of heavens, and the underworld and when in time the story of Lazarus and the rich man occurred is an entirely different discussion. The ancient Jews did have a sense of a ransom from the grave by God, but the specifics of their beliefs are murky in the Tanakh/Old Testament.) Caves were frequent sites for graves, which reinforced the connection between caves and the underworld even more.

Early Christians believed that those righteous inhabitants in the underworld were ransomed by Jesus Christ while he was in the grave and brought to a heavenly realm, so that now the only people left in Sheol would be the unrighteous ones. (Debate on the matter of the timing of the retrieval of the righteous dead has re-emerged in some Christian sects.) Pagans and some Jews believed that everyone was in Sheol, though pagans held that they were perhaps in different parts of it: the good people in a better place and the wicked in a place of eternal punishment. Most (but not all) Jews believed in heavenly kingdom in which the righteous would be rewarded and dwell forever, but whether that would happen after a bodily resurrection or it was an entirely spiritual existence was (and is still) debated. (Some modern Jews believe in no eternal soul at all–but again, that’s beyond the scope of this.)

But many other Powers that were not the shades of the dead also dwelled in the underworld or in the primordial chaos, especially those Powers connected to death and chaos. Every pagan cosmology enumerates many of them. The underworld is a place of giants, which were produced through some kind of miscegenation or had some monstrous aspect; of certain unnatural creatures (or monsters, but without quite the same fully negative meaning we now have); and of other gods (in the derivative sense), all of which are Powers.

But in most Jewish and all Christian cosmology, the only nonhuman Powers that would belong to in the underworld would be ones that weren’t belonging to the Creator’s court anymore–that is, the corrupt Powers who demanded worship and spread a corrupting influence over humanity. These would be the “fallen angels,” in the sloppier language of English Christianity, or the Watchers and the demons, to use other words from Jewish and Christian sources.

Therefore, in Judeo-Christian cosmology, going to a cave to seek divine interaction would be intimately linked to what we’d colloquially call demonic practices in English today. There could be no good that could come with trying to open oneself spiritually to the underworld. Simply being in any cave wasn’t sinister in the least–cave dwellings were handy places to sleep, after all, and they were long associated with holy groups that chose to live deliberately in extreme poverty. But a spiritual practice that sought to use the cave as a vehicle to connect to the lower realm was extremely sinister.

That is not to say that the Creator is unable to enter a cave or interact with people there. In the 1 Kings 19, Yahweh does just that with Elijah, who is in a cave for practical reasons of shelter. This chapter is a polemic against Powers that claimed ownership over caves–but it nevertheless reinforces that the Creator is he to whom heaven belongs, because Elijah is called out from the cave to stand on the mountain, which is the spiritually closest place to the heavenly realm. Little details like this are incredible important to understanding the scriptures and easily missed by modern minds that do not have these associations imprinted on them as strongly.

However, in pagan cosmology, all Powers are (by their nature) superior to humans. The rule of little-g-gods, in particular, is inherently correct because of that nature. There are some Powers that are more dangerous than others, but even they will have their followers, and it can’t be said in the pagan worldview that it is immoral for a human to devote himself to any Power. Even propitiating the most dangerous powers can be seen as a wise course of action. The most bloodthirsty of Powers could be the best ally a tribe could have. Therefore, even though there are certain clear negative connotations with the realm of the underworld even in the pagan worldview, it was considered entirely legitimate to attempt to spiritually connect with the Powers that were there.

So we have two very different pictures of what Muhammad’s cave-dreaming would be, depending on whether you are a pagan or a Jew/Christian. As a pagan, cave-dreaming would be a perfectly legitimate activity, especially if he wanted to gain some insight into the wellbeing of his step-son or his son who died in infancy. But in the Jewish or Christian mind, he was deliberately engaging in divination or witchcraft or whatever other name you want to connect to opening oneself to connection with corrupted Powers. In the New Testament, this was all lumped under the name “consorting with demons.”

It is no small wonder that Muhammad was viewed with some level of credibility by polytheists, who would see his source of revelation as legitimate, but was rejected by Jews and Christians despite their initial friendliness once they found out more about Muhammad’s circumstances and claims. The very circumstances of Muhammad’s revelation pointed directly to sinister, corrupt Powers to every educated Jew and Christian of Muhammad’s age–it had “consorting with demons” written all over it.

See the main page on Surah 96:1-5 to continue.