The rhyme of this surah is much rougher than other early surat that we’ve looked at, and there is just less consistency throughout, so there are marks of a number of stages of revelation here, though they’re quite a bit harder to tease out than they’ve been before.

The basic form of this surah has four sections, which were likely four distinct revelations, with some later revelations interpolating and modifying what there was before. The sections are Allah defending his oaths, some revelations about the transgressions of ancient people and the condemnation that Allah brought on them, the transgressions and condemnation of contemporary evil-doers, and the urging of the people toward obedience.

Allah Defends his Oath-Taking

Allah begins, as he often does, with shirk, swearing by a lot of things, and then he defends his choice of these things. In pagan poetry, people swore by things with power, so I believe the point of the swearing here, specifically the line that the discerning man will understand why these are sworn by, points back to the end-time signs that were revealed back in At-Takwir (The Overthrowing).

- By the dawn

- And ten nights

- And the even and the odd,

- And the night when it journeys on,

- Is there in that (not) an oath for him who discriminates?

The sun, as we already know, will be wrapped up (concealed) on the Great Day. Next comes the cryptic comment about the “ten nights.” According to the unanimous opinion of Islamic scholars (not merely the consensus), this refers to the first ten nights or ten days of the Dhu al-Hijjah (in the Islamic calendar), the Month of Pilgrimage.

Narrated Ibn Abbas: The Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) said, “No good deeds done on other days are superior to those done on these (first ten days of Dhu al-Hijja).” Then some companions of the Prophet said, “Not even Jihad?” He replied, “Not even Jihad, except that of a man who does it by putting himself and his property in danger (for Allah’s sake) and does not return with any of those things.”

al-Tirmidhi

This may be the remainder of an early belief of Muhammad that the Great Day would be coming very soon at the Festival of the Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha) that begins on the 10th day of the month–certainly another pagan holdover.

The “even and the odd” seems odd to most readers, but again, when we understand At-Takwir (The Overthrowing), it’s suddenly very clear. Muhammad thought that the phrase “as it was in the days of Noah” meant that animals would pair up right before the Great Day. Therefore, throughout the Quran, there is the assertion that 1) all life exists in pairs except for Allah himself, and 2) the existence of these pairs is a sign for the people. Here, Allah is swearing by the even (all life in creation) and the odd (which is himself). Muhammad saw a profound mystical significance in this, distinguishing the Creator from the creation and therefore reinforcing his belief is the perfect oneness of Allah. To his mind, if there was such a thing as a trinity (which he could only understand as a triad of gods), that would undermine this Creator/creation distinction. A good deal of Islamic doctrine spins out from the simple misunderstanding of a cryptic line in the second- or third-hand apocalyptic account that Muhammad had heard.

The swearing by the night again has some echo of the apocalypse of at-Takwir.

These are all things that are or will be signs to the people, so Allah declares that the discerning or discriminating man will see in these oaths religious meaning.

The List of Trangressors

- Did you not see how your Lord dealt with ‘Aad,

- Iram of the pillars,

- The like of which was not created in (all) the lands,

- And Thamud, who clove the rocks in the wadi,

- And Pharaoh, he of the stakes,

- Who (all) transgressed in the lands

- And multiplied corruption therein?

- So your lord poured on them a scourge of punishment.

- Indeed, your lord is ever on the lookout.

This is a list of people who have been previously condemned for their evil deeds. I will get to their specific stories in a moment. However, first, we need to look at ayah 12. It abruptly breaks the rhyme of the surah so far, and so it shows all the signs of having been inserted later. I believe that this is to make surah 89 echo surah 5:32-40 more closely. When Muhammad begins butchering the Jews around Medina, he says that they are guilty of two crimes: spreading corruption and transgressing. Surah 89 only had “transgressing” before this point, so adding “corruption” (which was itself an alteration to the actual rabbinic proscription, but was give a priority of place in surah 5) harmonized the kinds of evil deeds for which divine retribution is deserved. (There are more echoes in words and phrases between the two surah, like the scourge of punishment and so on, but surah 5 probably drew from the extant surah 89 at that point.)

‘Aad/Iram and Thamud are from Arab history and legend.

‘Aad is a location in Southern Arabia in the “sandy plains” or the “dunes.” Imran may be the name of a place or a name of a people who had a city there. ‘Aad got connected in late Islamic lore to the people of Thamud, which caused some confusion, but in the more ancient sources, they are definitely a people of southern Arabia–I would connect them to the people who spoke the ancestor of the Modern South Arabian language. Imran was the name of a tribe that was in Oman by the time of Ptolemy.

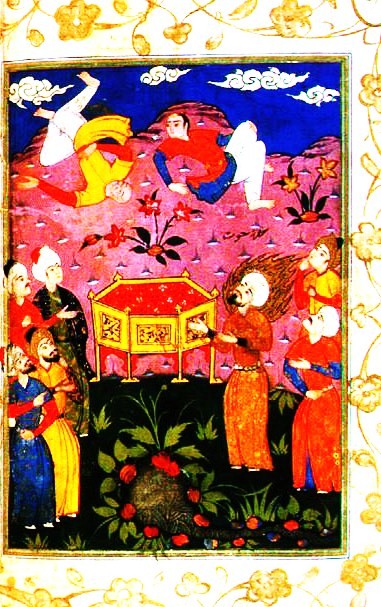

The Islamic myth goes that they were the first builders of cities in southern Arabia. At some point, the prophet Hud came to them, declaring monotheism, and the people of ‘Aad killed him. As a result, they were destroyed by a great wind. Various sites are revered as the tomb of Hud, including in the Hadhramaut, in Damascus, and even in the enclosure of the Kaaba.

The myth of the fabulousness of a city of ‘Aad (which acquired the name Imran) grew in Islamic folklore until it reached the level of the myths of Cibola in the Americas or Atlantis in Greece. However, there’s no basis for this in the ancient stories.

None of the firsthand pre-Islamic accounts of ‘Aad, Hud, or Imran survive, though they are certainly based in pre-Islamic legend, so it’s unknown how many liberties the Islamic version of events took with its source material. Given the freedom with which early verse and primary sources are quoted in other contexts, I suspect the reinterpretation was substantial.

Thamud became associated with the remnant of ‘Aad in Islamic tradition, but this is almost certainly wrong. They were a northern Arab tribe of the northern Hejaz and the surrounding regions, quite distantly related from either of the two South Arab groups. History also places the ‘Aad in the general area of Yemen before about 1600 BC, moving eastward afterwards, while the earliest reference to the Thamud tribe is from 715 BC.

The Thamud here are being associated with the Nabataean cities of Hegra (meaning “the rocky place), this is not accurate–the Nabataeans were a different, settled tribe who expanded into the area of the Thamud and founded the rock-carved houses there in the 1st century AD.

The legend of the Thamud concerns the prophet Salih, who is purported in the Quran to be another monotheist prophet. His story is both more detailed and more bizarre, as recounted later in the Quran:

To the Thamud people (We sent) their brother Salih. He said, “O my people! worship Allah: you have no other deity other than Him. There has come to you clear evidence from your Lord. This is the she-camel of God sent to you as a Sign. So leave her to eat within God’s land, and do not touch her with harm, lest there seize you a painful punishment.And remember when He made you successors after ʿĀd and settled you in the land, and you take for yourselves palaces from its plains and carve from the mountains, homes. Then remember the favors of God and do not commit abuse on the earth, spreading corruption.” …

So they hamstrung the she-camel, and were insolent toward the command of their lord and said, “O Salih, bring us what you promise us, if you should be of the messengers.” So the earthquake seized them, and they became within their home (corpses) fallen prone.

Q. 7:73-74, 77-78, Pickthall translation

This is an obvious reworking of a pagan legend involving a sacred camel, but it was taken into the Quran as another prophet of God who was rejected by the people, who brought upon themselves a terrible earthquake.

There were terrible earthquakes, but the affected the Nabataeans, who lived in the stone houses, not the Thamud, who were a largely pastoral tribe. At any rate, the Thamud had disappeared as a tribe by about AD 400, while the Nabataeans were still kicking around, and the Thamud had become one of the legendary tribes of ancients about whom stories of old could be told.

Because of the confusion caused by the Islamic sources, just as the people of ‘Aad get wrongly associated with northern Arabia, so the people of Thamud get wrongly associated with southern Arabia. But the earliest legends match the Greek sources, who know of both the ‘Aad and the Thamud and place them correctly in their general locations at that time on the Arabian peninsula.

“Pharaoh of the stakes,” or “Pharaoh, he of the stakes” refers to the Quran’s assertion that the pharaoh who ruled in Egypt had the practice of crucifying people (a Roman practice of some 1200 years later). There is more about the crucifying pharaoh of Moses later on, of course.

According to Allah in this passage, all of these people were punished severely for their transgressions (and after the later revelation, for multiplying corruption, too). The phrase “ever on the lookout” has the sense of keeping a lookout while lying in ambush.

The Present Transgressions of the People

The first two revelations were pretty straightforward in their composition, probably revealed one after the next, with only a small interpolation later. The next section, however, is a mess. Rather than simply mark the latest addition, I’m going to put build up this section as the rhyme, length, and content indicates it was revealed.

Version 1, with a consistent rhyme:

- Nay! but you (all) consume the inheritance, devouring (it) altogether,

- And you (all) love wealth with an abounding* love.

- Nay! When the earth is leveled out, grinding (upon) grinding,

- And your Lord comes, and the Angels, rank (upon) rank,

- So on that Day, none shall punish as he punishes,

- And none shall bind as he binds.

The Quran is preoccupied with the idea that the Great Day will be marked by the land being made completely level. I believe this comes from the Harmonized Christian Apocalypse that Muhammad had access to when writing At-Tawkir, but once again, lack of context makes it take on a strange, specifically Islamic character. At this point, Muhammad doesn’t yet realize that it’s Jesus coming with the angels–after all, he just had a throne vision of Allah, so surely Allah would be the one coming in person.

Most Muslims don’t realize that the Quran is equating Jesus with God here, because that’s just what the source that Muhammad knew did!

The ultimate source for this is Isaiah 40, in a passage repeated multiple times in the Gospels:

3 A voice cries: “In the wilderness prepare the way of the LORD; make straight in the desert a highway for our God. 4 Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain. 5 And the glory of the LORD shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the LORD has spoken.”

Isaiah 40:3-5, ESV

This is a metaphorical passage to Christians and Jews. Christians are told in the Gospels that this was accomplished by John the Baptist, but many Christians also believe(d) that there will be a kind of recap of this event in the end times, so this was probably in the apocalyptic Christian source from which so much of Islamic end-time events come.

In contrast, the Quran sees this event as precisely literal, however–a very specific event of the completely flattening of the earth on the Great Day. This made sense to Muhammad because he also believed that the world was flat to begin with, so a hyperliteral flattening of something that was broadly flat to begin with makes more sense, especially to one unfamiliar with the poetic language of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. The Quran should never be regarded as figurative or metaphorical–that sort of thing was anathema to Muhammad, who repeated asserted that the Quran said exactly what it meant in the plainest terms.

The “binding” is also present in Christian and Jewish thought, and explicitly in Christian scripture. It almost certainly comes from the Harmonized Christian Apocalypse, as well.

In 2 Peter 2:4, we read, “For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment…” In Jude 1:6, we read, “And the angels who did not stay within their own position of authority, but left their proper dwelling, he has kept in eternal chains under gloomy darkness until the judgment of the great day…”

This idea is most fully fleshed out in the Book of Enoch. Enoch is not a part of the Hebrew or Christian scriptures, but it lays out many of the thoughts behind inspired Christian and Jewish doctrines.

- Again the Lord said to Raphael, Bind Azazyel hand and foot; cast him into darkness; and opening the desert which is in Dudael, cast him in there.

- Throw upon him hurled and pointed stones, covering him with darkness;

- There shall he remain for ever; cover his face, that he may not see the light.

- And in the great day of judgment let him be cast into the fire.

- … And when all their [the rebellious angels’] sons shall be slain, when they shall see the perdition of their beloved, bind them for seventy generations underneath the earth, even to the day of judgment, and of consummation, until the judgment, the effect of which will last for ever, be completed.

- Then shall they be taken away into the lowest depths of the fire in torments; and in confinement shall they be shut up for ever.

- Immediately after this shall he [another demon], together with them, burn and perish; they shall be bound until the consummation of many generations.

This idea is also recapped in the Book of Revelation, when the fallen angels are thrown into the lake of fire. Muhammad doesn’t know that this “binding” refers to the being commonly called “fallen angels,” however–in Islamic doctrine, it’s the unbelievers who are bound by the guards of hell. This misunderstanding points again to the condensed Harmonized Christian Apocalypse that Muhammad knew.

Next came Version 2, with bits added that break up the rhyme but no excessively long dumps yet:

- Nay! but you (all) do not honor the orphan,

- And you (all) do not urge the feeding of the poor,

- And you (all) consume the inheritance, devouring (it) altogether,

- And you (all) love wealth with an abounding* love.

- Nay! When the earth is leveled out, grinding (upon) grinding,

- And your Lord comes, and the Angels, rank (upon) rank,

- He will say, “O! I wish I had sent forth for my life!”

- So on that Day, none shall punish as he punishes,

- And none shall bind as he binds.

This clarifies more what people are supposed to be doing with their wealth, and it also adds the doctrine that the Muslims were living in the last days, with their last chance to give charity and pray to be saved from Hellfire. During Muhammad’s lifetime, he taught that charity and prayer were good deeds sent before you to save you from hell, while you should pay for every evil deed that you have done on earth before you die to make sure that you don’t have to pay for them after death.

This was really the whole of Islamic doctrine early in Muhammad’s career, as he thought that doomsday was truly imminent, but this doctrine evolved over time, especially after the migration to Medina.

Version 3, with the long dumps and the addition of the “reminder” doctrine:

- And as for man, whenever his Lord tests him and honors him and favors him, then he says, “My Lord has honored me.”

- But when he tried him and straitened his provision, then he said, “My Lord has despised me.”

- Nay! but you (all) do not honor the orphan,

- And you (all) do not urge the feeding of the poor,

- And you (all) consume the inheritance, devouring (it) altogether,

- And you (all) love wealth with an abounding* love.

- Nay! When the earth is leveled out, grinding (upon) grinding,

- And your Lord comes, and the Angels, rank (upon) rank,

- And Gehenna is brought (near) that Day, that Day man will remember, and how shall the reminder be for him?

- He will say, “O! I wish I had sent forth for my life!”

- So on that Day, none shall punish as he punishes,

- And none shall bind as he binds.

I believe that this edit is of a late Meccan/early Medinan date. Here, there is a reference to sufferings in the material condition of Muhammad’s followers. This was not a concern in the earliest years of Islam, when Muhammad was convinced that the Great Day was going to occur at any moment, and he wanted people to spend their money on charity quickly.

Once Muhammad’s followers lost their positions in society, Muhammad had to contend with the pagan belief that gods who are pleased with people make them rich and successful and gods who are displeased always smite them. After all, even in the context of the surah, if you were asking, “Who exactly is God smiting right now?” your answer would not be the pagans of Mecca, who are still happy and well off. These ayat turn that around, asserting that wealth is a test of charity rather than an honor, and the person without wealth is actually being spared this test or trial. After all, if you’re poor, then you would be receiving charity from the faithful followers of Muhammad rather than being obligated to give it out of fear of the hellfire!

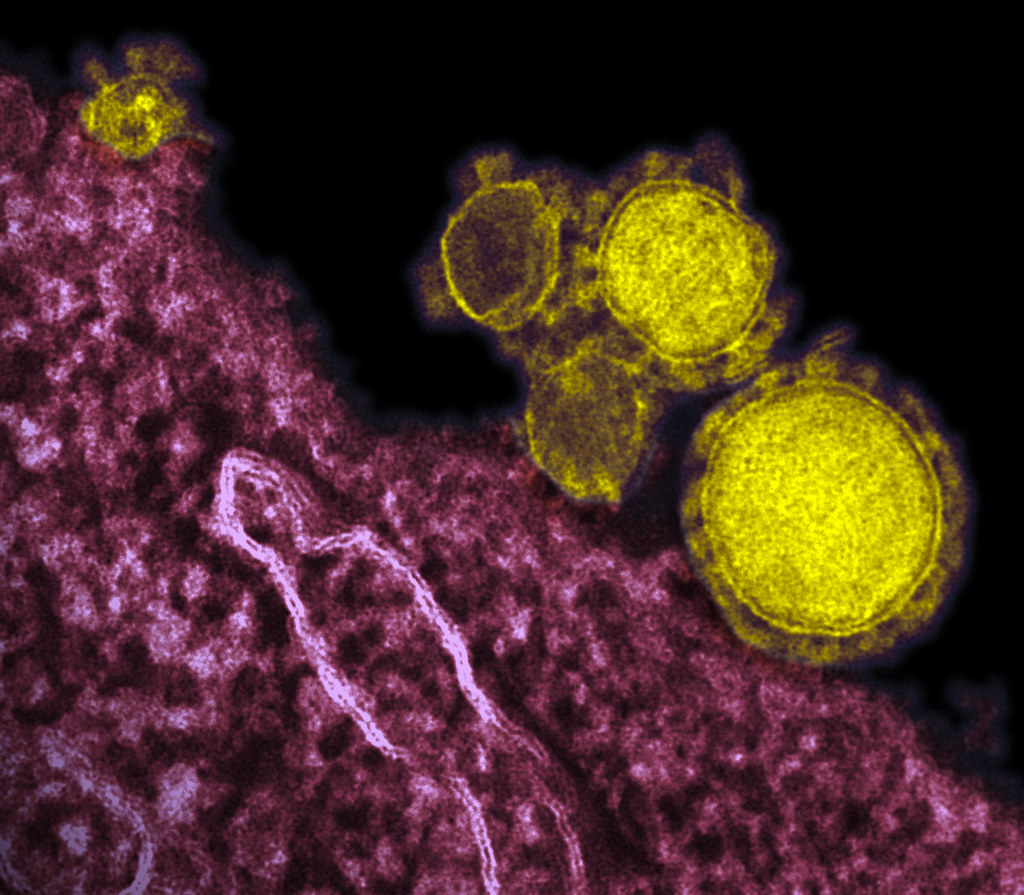

Gehenna is the word most often used for Hell in the Quran and Islamic sources (when the word Fire is not used instead). Gehenna is a valley in Jerusalem where some of the kings of Judah, in defiance of God, set up a pagan temple to Molech, where they sacrificed children by fire. Later, it became the garbage dump of Jerusalem, and it was considered a cursed place.

In ancient Jewish literature, this name was then taken by extension for the place of eternal punishment of the wicked dead, which is distinguished from the more generic Sheol, or the land of the dead, where everyone went in Jewish thought with an eternal hope of future ransom for the righteous. It is used in this sense by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and James. Therefore, it is the legitimate and expected proper name for Hell as used by speakers of Semetic languages. The word Gehenna was probably not in the Harmonized Christian Apocalypse, however, as Muhammad initially called Hell only “the Fire” and then the inscrutable “Saqar” that literally no one understood, and Gehenna only appears in this and other considerably later sources. This is clearly after Muhammad has had more familiarity with Judeo-Christian ideas than he had initially.

The idea that Hell will be brought near is much harder to decipher. This is, as one would expect, absolutely literal in the Quran.

Abdullah ibn Mas’ud narrated that the Prophet said:

Hell will be brought on near that Day and it will have seventy thousand leashes, and each leash will have seventy thousand angels pulling it.

al-Tirmidhi

There is no basis for this in any scripture or in any Jewish rabbinic tradition that I could find, Talmudic or otherwise. This appears to be an artifact of Muhammad’s understanding of the Harmonized Christian Apocalypse–like the line “as it was in the days of Noah,” it was something that could be easily misunderstood without the full context. It is unfortunate that no trace of this document seems to have survived outside of the Islamic sources.

The Conclusion

Many of the surat have a brief sort of conclusion or postscript, and this is no exception.

- O creature who is satisfied!

- Return to your Lord, well-pleased, well-pleasing!

- “So enter among my slaves,

- And enter my Garden!”

This conclusion, though its rhyme is shaky and it feel a bit tacked on, was obviously revealed before Islamic doctrine took a hard turn toward determinism, because in this passage, the person being addressed is being urged to respond to Allah’s call with the understanding that they will be able to do so.

Ibn Abbas narrated (as recorded in the Tasfir if Ibn Kathir), “This ayah was revealed while Abu Bakr was sitting (with the Prophet). So he said, ‘O Messenger of Allah! There is nothing better than this!’ The Prophet then replied, ‘This will indeed be said to you.'”

Of course, the term ‘Allah’ was anachronistic at this point (it’s anachronistic now as I use it here, but it’s a convenient term), so that was clearly a later interpolation, but if it’s true, that pushes this even after Abu Bakr came back from the winter caravan to Yemen and began to follow Muhammad.