One of the things that Muslims like to say about any criticism of the Islamic requirement to wear a hijab is that Mary, the mother of Jesus, wore a veil, and so Christians who criticize Islamic veiling are at best ignorant and at worst hypocrites.

Now, there is nothing in the Bible about Mary wearing a veil. It isn’t in the Injil (Gospels) or in any of the Epistles (letters) or any other part of the Bible. So why do Muslims think that Mary wore a veil?

The reason is pretty simple. Mary does wear a veil in a lot of Christian art. But they have a bit of a problem, because Mary also doesn’t wear a veil in a lot of other Christian art from the very same time period.

This painting, by the anonymous Master of the Saint Lucy Legend, was painted around 1500. It depicts Jesus on the lap of Mary, his mother, who wears the crown. St. Catherine is receiving a ring from Jesus on the left and St. Barbara holds a carnation on the right. Mary Magdalene is kneeling with a pot of ointment. St. Ursula reads a book, St. Apollonia has a pair of pincers with the tooth, and St. Lucy is holding a dish. The saint with the white headdress is unknown–my guess is the Dutch saint Godelieve. St. Agnes has the lamb, and possible Christina has the cradle, and St. Agatha has the pincers with the breast. St. Margaret in the black headdress has the cross.

It is a painting for a church, attended devout Catholic audience. Notice many veils? St. Margaret has one–because she is married. (If the woman in the headdress is Godelieve, one of the few female saints with a crown as a symbol at the time it was painted, she was also married.) All the other unveiled saints were unmarried virgins or (like Mary) considered a virgin.

Muslims can’t explain this because they don’t know what a veil signified in pre-Islamic Mediterranean society…which was the same thing that it continued to signify in Western Europe for hundreds of years.

But it’s actually straightforward. A veil was originally something that was only worn outdoors in public, and its primary meaning was that a woman was a married freewoman. Slave women were not permitted to wear veils, and just as significantly, unmarried women didn’t wear veils. Veils did not serve to make women less sexually tempting to men or to protect them from assault. Even the daughters of the most important men—senators, the emperor, the high priest, whoever—would not wear a veil before they were married, with extremely few exceptions that don’t even belong in this video. Even among the Talmudic Jews, who invented extreme gender separation in the centuries after the ministry of Jesus Christ, veiling began at marriage, never before. It’s also important to remember that in the time of Jesus, veils were worn when out in public spaces, not usually when women were in their own homes, even when women were entertaining non-family men there.

Later Christian society, especially in the West, generally followed this same convention until the middle of the 16th century, with variations as fashions changed. I’m not going through all the ups and downs of 1600 years of fashion history, but if you keep this in mind as a basic rule, you won’t go far wrong. Related to this is a custom that I think comes from European barbarians that unmarried girls also typically wore their hair loose or down, and married women wore their hair more contained or up—wearing the hair down until marriage doesn’t seem to be a specifically Roman or Jewish tradition, so when we see loose hair as a symbol of virginity in Western art, it probably has a Western barbarian cultural origin.

Anyway, in the first 1500 years or so of Christian art, Mary was shown generally wearing clothes that were typical of women in her position in contemporary society or from an earlier but still Christian era. If Mary was married at the time of her life that an image is depicting, she is usually shown with the type of head covering that married women wore then or at some point in the Christian past. If she is shown before she was married, she is shown either without a veil at all or with the sort of headdress that unmarried women wore at that time of the painting—usually, this headdress was see-through, or her hair was very visibly loose underneath it, which signals that she’s not married and obviously doesn’t conform to any standards of veiling for the sake of modesty.

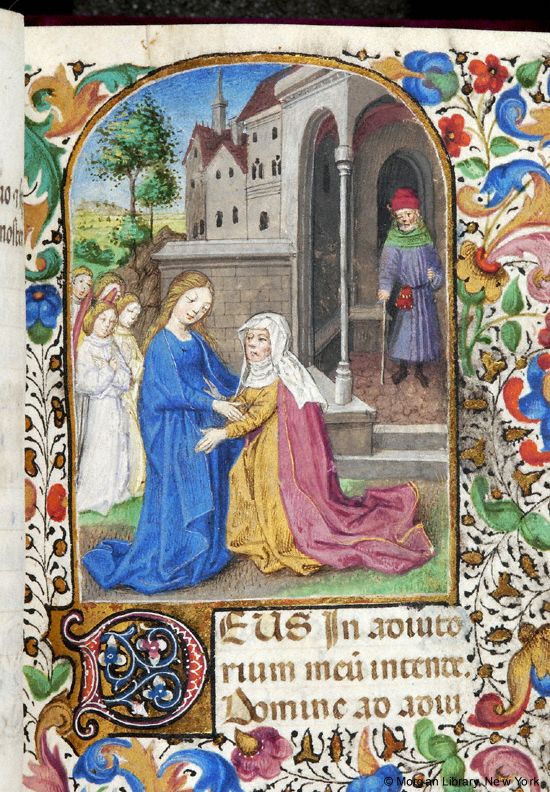

Here is Mary on the left visiting her cousin Elizabeth on the right. Unmarried, Mary wears no veil on her head.

Here is unmarried Mary with married Elizabeth again.

Here Mary gets a fashionable headdress–with loose, visible hair showing that she’s a virgin.

The emphasis on visibly loose hair even under a veil in a scene where she was married was a way of pointing to the medieval church doctrine that Mary was an eternal virgin. Sometimes, this goes as far as aggressively depicting her with no veil at all at a point in situation in which she would have actually worn a veil! It’s still not indecent or immodest. A combination of the veil and loose hair–a combination that never would have been worn in history by a married woman–became the conventional image of Mary that you end up seeing in a lot of representations of Mary from the 18th century and later, but most of the artists now don’t even know why they’re repeating these themes or what they meant to the people who originally came up with them.

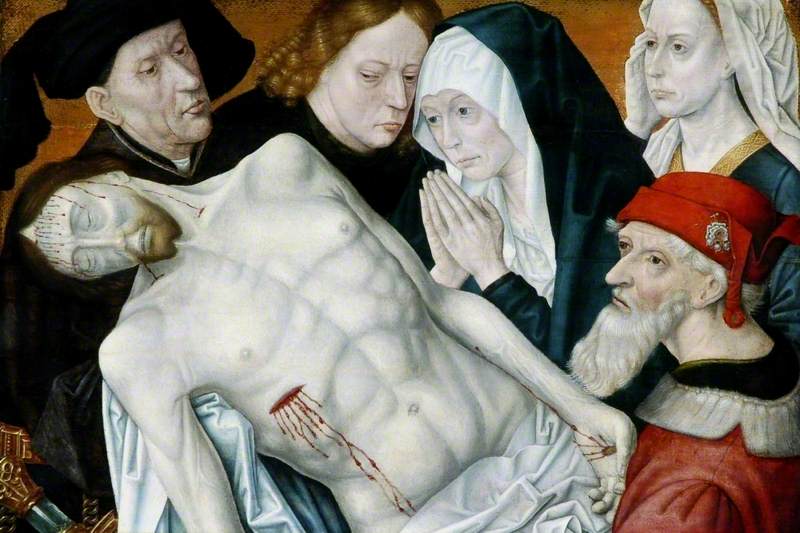

For the same reason, sometimes Mary was shown with clothes that resembled a nun–most commonly at a lamentation scene at the cross.

Furthermore, when Mary is pulled out of the context of her life and shown as the queen of heaven, a title the church gave her in AD 431, she usually loses the veil of her temporary earthly marriage completely and gets a crown to replace it instead, still with the loose hair of a maiden, because it is Christian doctrine that people are not married after death. Related to this doctrine of the queen of heaven, Mary is typically shown dressed in mostly blue, the color of the sky, which came to represent purity, as well. Jesus Christ, in contrast, is usually represented in red, the color of blood and also of love. So sometimes Mary’s clothes are red, instead, to show the connection between her and Christ. Often they are both blue and red.

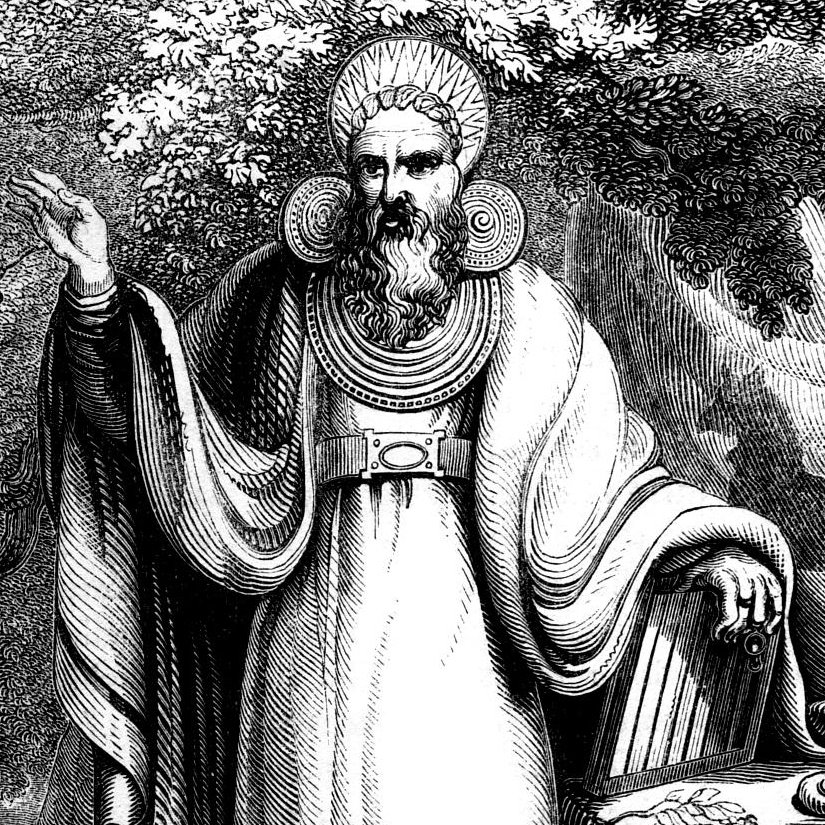

Now, in the Eastern Orthodox Christian sphere, religious images are mostly much less naturalistic and much more formal, with a kind of freezing of the portrayal of Mary in early medieval Byzantine clothes. The image of Mary that is used practically everywhere is one from the theodokos, or Christ-bearer, which is a formal picture of Mary with the Christ child, showing that she was the vessel through which Jesus Christ entered the world. Obviously, at this time, she was married, and so she has an early medieval veil. This Mary-as-a-mother is then used in every Orthodox icon of her, regardless of the setting. This is a product of Eastern iconography, not some statement about Mary being always veiled.

Even in the Orthodox tradition, we see what the normal clothing for proper and modest maidens was considered to be in portraits of saints who died as virgins and, perhaps most usefully of all, in the antique portrayals of the Ten Virgins in one of the parables of Jesus. There are a few exceptions, especially when an illustrator is trying to be historical but doesn’t really know how, but overwhelmingly, even more than a thousand years after the life of Christ, these basic and very ancient patterns remained: married women and nuns covered their hair, but unmarried women didn’t.

So, did Mary, the mother of Jesus, wear a veil? Well, she certainly wore one in the way women of that time and place usually wore them—in public, after she was married, in a way that covered the top of her head and the back of her neck but did not obscure her face, hide all her hair, or cover her neck. Though they are much stricter about hiding all the hair in the presence of any non-family men, Orthodox Jewish women today preserve this tradition the best, taking it from the same cultural environment as in Arabia before the Quranic commands concerning veiling.

This is an important point because the veiling of Muslim women does not come from a continuation of ancient tradition but instead with a sudden and sharp break from it. The orthodox Islamic view is that everything that is meant to be covered by a veil is a private part of a woman, as indecent as if a man were walking around with his genitalia out. And the most unhistorical and least restrictive of standards require that a woman cover everything except her hands and face, while the more historically correct requirements only allow her hands as much of her eyes to be uncovered as it is necessary for her to see her way. I’m not going to get into the proofs for that here, but I will be making other videos on veiling later, and I’ll be linking them below as they come out.

I will just say that these images of Mary, which are in the very tradition that Muslims argue that prove that Mary was veiled like Muslim women are veiled, would be indecent or obscene according to all Islamic standards. Even the images in which Mary wears a veil almost never show coverage to the same level that even the most liberal interpretation of Islamic sources require.

Yet there is nothing offensive or indecent or immodest about any of these portrayals of Mary. Not even the ones where Mary is shown providing milk in a representation of Christian charity. These are all paintings that are meant to venerate Mary and show her as a highly virtuous woman to be admired and respected.

So yes, in many images, Mary wears a veil because all married women wore veils in public to show that they were married, in a tradition that came from the common practice of the Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East. That’s about as exciting as arguing that someone in the West wears a wedding ring today. But she did not wear a veil before she was married. She did not wear a veil because the hair of a woman is a private part. She did not wear a veil so that she wouldn’t be harassed or assaulted. She did not wear a veil because a man might look at her and feel lust.

So did Mary wear a veil? Sure, after she was married. Did she wear a hijab, with all that it means? No. Not even close.

Mary did not wear a hijab.